Lal-sar-Jangal – early winter 1989

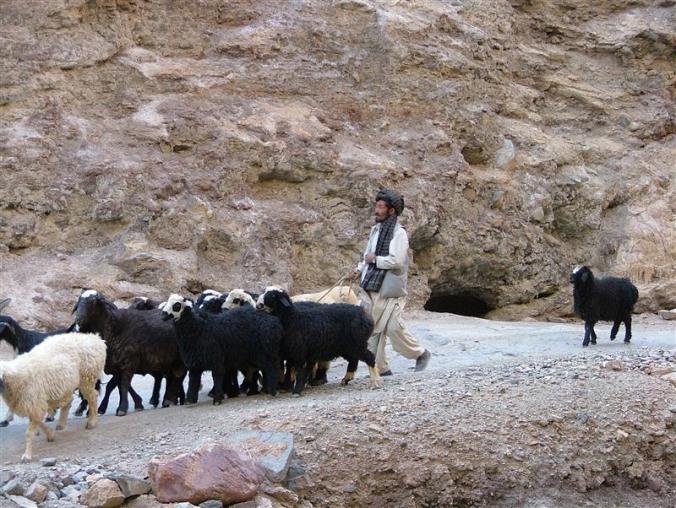

I’ve included a selection of random photos in this post.

On the ride home from the school visit Ibrahim complained about Qurban’s absence, saying this was typical of his behaviour with the people in Lal. ‘He does not understand it is important to keep these people happy – the teachers, the Commanders, the Mullahs. If they are happy the work will go well but if we upset them they can make trouble for the clinic. They care about their position being respected and Qurban should understand this.’

I decided to talk to Qurban. He was unrepentant about not turning up at the school, ‘Ibrahim behaves as if he is in charge, always talking to the people at the paygar (local government office), being friendly to the Commanders.’

‘Qurban, it’s called public relations. It is important. If the headmaster is upset with you and complains to the Commanders they could make problems for you and for the clinic. It’s surely not asking too much to spend some time now and then to keep them smiling. They know you are in charge of the clinic, not Ibrahim, and if you don’t accept their invitations they feel insulted.’

‘So let Ibrahim do this work and I’ll do my leprosy work,’ Qurban shrugged.

‘That’s not the point. Ibrahim is your assistant. The “bazurg” (big people) expect the most senior person to meet with them.’

Since I was already steamed up about one issue, I continued, ‘Another thing, why do you behave so badly when we are together at mehmanis (dinner parties) – not speaking to me, acting like I have done something terrible. I admit I don’t always understand the customs – but if I make mistakes it would be better to tell me about them.’

‘I don’t have to explain my behaviour to you.’

I gave up and turned to leave but, as I reached the door he called me back. ‘Listen! Our people are very poor. Most of them can’t afford more than dry bread and tea – every day. Some people can eat meat maybe once a month, others, once a year. They work hard on the land but there is never enough wheat for the winter. Do you know that sometimes in the winter the poorest people have to eat grass from the mountain, because they have nothing else?

‘I want to help my people but I can’t put food in their mouths, all I can do is try to make them better if they are sick. Sometimes we give some money from the social budget to a poor leprosy patient who can’t work but there is not enough money to help everyone. Besides, many people who don’t have leprosy are even poorer. You have been here for nearly two months, you must have seen this for yourself?’

‘Yes, I have seen the poverty – although I have never seen people reduced to eating grass.’

‘Well, it happens. People hope to be able to afford new clothes once a year for Nau Roz (Afghan New Year). It is the only time they can have something nice to wear. They wear the same clothes until the next year. These are my people, I work for them, and I really try to help. ‘Then, a foreigner comes along and everyone wants to meet him, or her. They invite them to their houses, kill a chicken for them – give them as much meat in one meal as would feed a poor family for a week. The people make a big fuss of the foreigner; their hopes are raised because they know foreigners have money, and the power to change things.

‘Then the foreigner says we should teach them this and teach them that and not give so much medicine to them. The foreigner bashes away on her typewriter making reports, then goes away and nothing changes.’

He shrugged, ‘Sometimes it makes me crazy. I don’t have power like the Commanders. They are rich, maybe even as rich as you, but do nothing for the people. They demand respect without doing anything to earn it – and expect me to run around them telling them they are wonderful.’

Qurban finally ran out of steam and I sat, stunned, wondering how to reply. ‘I understand some of what you feel,’ I said quietly, ‘and I feel guilty about how much people spend to prepare a dinner for me but what can I do? If I refuse their invitations they will be hurt and offended, won’t they?’ He nodded in silent agreement.

I continued, ‘We work for a very small organisation. We can’t do much more than we are doing already. As we are not agricultural experts, we can’t teach the farmers how to improve their crops. We can only try to persuade other organisations to come and do these things. By visiting the clinics I can provide first hand reports for the donors, persuading them to continue their support. That is the way in which I am most qualified to help – by writing about the needs of the people. I am sorry that you feel my presence is such a burden on them.’

Qurban smiled faintly, ‘Yes, the money is important. I suppose the occasional chicken is an investment – keep you happy so you keep the donors happy.’

‘The donors don’t count the chickens that are killed for me. They judge the success of the project on the number of leprosy patients you find and treat, the number of other patients coming for consultation and, of course, they are keen to see that we can work freely without trouble from political Parties.’

A few days later, the headmaster, with some of his teachers, paid a return visit to the clinic. Qurban played the part of clinic In-charge and host to perfection, smiling, courteous, a role model for all future public relations encounters. The headmaster was extremely deferential towards him. When they left, I said to Qurban, ‘You see it is not difficult to keep these people happy. They were all very respectful to you.’

Qurban looked at me pityingly, ‘You don’t understand anything about the people here. They can very easily pretend to like and respect someone, but I know what they are thinking. When they see me they think of leprosy. If people behave as though they like me, it is because they feel sorry for me. No-one sees the real Qurban so how can they know if they like or dislike me?’

I wished I had a degree in psychology, to help me understand what went on in his head – more importantly to know how to help him.

It seems like there is no good answer. You were doing your part as was he. Maybe a psyc degree would help.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think it might, but more importantly to know how to help him. The stigma from having leprosy as a child had gone really deep.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That is so very sad.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Another educational post from you, Mary. Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, John, for still taking the time to read and comment.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Who could stay away?

LikeLiked by 1 person

In social situations, it’s not important that people like you as a person, it’s important that you serve the purpose you signed up to do. Creating work connections between people who you would not otherwise socialize outside the workplace can open doors to places otherwise closed to him. He seemed reluctant to push aside the past humiliations he had endured in order to achieve his goal. Even without a psych degree it looks to me as if you helped him to take the first step to creating work connections

.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for your comment, especially the last sentence. I always felt I failed Qurban in some way but spending three months with someone is not long enough to unpack all his past humiliations and perceived humiliations of the present. When not in a deep depression (and I think he was probably bipolar) he was a truly lovely guy – caring, good humoured, amusing…

LikeLiked by 1 person

How very sobering. We all learn to play a role when we try to advance our goals, don’t we? learning how to do that under the rules of a different culture is very hard to do! Such a sad and interesting post!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, it certainly made me pause to reflect on a lot of things to do with my role and the complexities I hadn’t understood.

LikeLike

I don’t think that a “degree in psychology” would have been nearly as useful as you being there, feet on the ground—sharing and learning and showing by your very presence how much you care. You had already gone so far beyond anything that psych degree could ever have provided.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks for your kind words, Barb. I think I was a disappointment to Qurban when I arrived in Lal. When we were both in Karachi, where he was a paramedic student, I was his big sister and his teacher. He was the first person to take me to the cinema, I was at his wedding, he confided in me. Then, I arrived in Lal, struggling to understand the culture, not fluent in Dari, not even able to ride a horse but, because of being a foreigner respected by all and sundry. It was all very complicated and added to that was all he had suffered as a child with leprosy.

LikeLiked by 2 people

He seems such a wounded soul, do you still hear about him?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think you have described him perfectly – ‘a wounded soul’. I occasionally hear snippets of news. He is not with the organisation now and I last heard he is back in Karachi in Pakistan. Maybe someone will tell him about this blog and he’ll appear to shout at me 🙂

LikeLiked by 2 people

That would be cool!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve been amazed at the number of people who have got in touch, usually through Facebook, to say they recognise places and people in the posts or who tell me their parents remember me.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s really nice,good to be remembered!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Mary, you have really highlighted that we go to help but we have no idea if we could be making matters worse. If only there were books about culture – if we ever get to understand them and the way that different mindsets and culture think and behave. I remember hearing that African men walked in front of the women to protect (from way back). Once I knew this I didn’t resent them pushing their way out fo the lift in front of me. a small thing, but it made a difference.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks your on-the-nail comments, Lucinda. Speaking of books on culture, in Pakistan there was a pamphlet produced by a British women’s group on the ‘culture’ designed to help new arrivals. It was a horrific publication which began with the premise that all servants were dishonest and gave tips on how to stop them stealing food, falsifying accounts, etc.

LikeLiked by 2 people

That is horrible. It never ceases to amaze me how ignorant some people can be.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s when you realise that travel does not always broaden the mind!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Exactly!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Another wonderful post Mary, and so difficult to walk that tight-rope of diplomacy. You did a great job though judging by the return visit of the headmaster… Totally in awe of those surroundings and the people who had so little but went to such lengths to show their hospitality..I have pressed for Tuesday..x

LikeLiked by 3 people

Thank you, Sally. Life there did often feel like walking through a minefield (sometimes literally!), holding my breath, waiting for the explosion. Sometimes when the diplomacy ran out, I was the one exploding, but mostly, I think I did manage to keep what we call here, a calm sough. Thanks for sharing.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Pleasure Mary.. I am learning so much about Afghanistan from your posts. x

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reading Qurban’s words, I get some sense of his frustration, and his atitude to the foreigners who did their best to help, but could always go home at some stage. For a long time now, part of me has thought that we should never have intervened in any of those countries, and left them to their own culture and to try to solve their own problems. But given our sense of humanity and compassion, I suppose that was never going to happen.

Best wishes, Pete.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I totally got Qurban’s frustration. Our best could never be enough. It’s a valid argument that we should not try to help (intervene/interfere) and one I’ve often thought about. If we weren’t there with sticking plasters, would the people eventually decide enough was enough and demand their governments do something? I don’t know the answer.

LikeLiked by 2 people

It’s a tricky one, isn’t it?

LikeLiked by 1 person

A heartfelt episode in your story. I can see this man was trying to do his best for his people in spite of his own issues. We can never really walk in another´s shoes, can we?

LikeLiked by 1 person

You are right, Darlene, we can’t. Qurban certainly made me think about my role and about how foreigners are viewed. Our presence leads to expectations we can never meet. Is doing something, however, little, better than doing nothing?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I will always believe that doing something is better than doing nothing. I think Mother Teresa said something like this. “Small things done with great love will change the world.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

Mary, my degrees are in Psychology and I can’t claim that I would have been able to give him more help than you. You have natural empathy and you really care. Like that first ray of sunlight after a storm, you do give them hope and no, none of us, whatever our background can give them all that they need.

If you go back and read this post, you will see how, even if only briefly, you gave him a focus beyond his own suffering. That in itself is a huge gift. Another gift is helping them discover some choices they could make which may create a different outcome, Empowerment is a powerful tool when one feels helpless. Therapists, even the best ones, can only listen, give feedback, and plant seeds that we hope to nurture. The individual has to work with us and want to change. That is huge as most people fear change. Thank you once again for that window into another culture which is something that has fascinated me since I was a very young girl. xx

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much for your very generous comments, Lea. I really appreciate them and I am pleased my posts let you glimpse through a window into Afghanistan and its messy, complicated, wonderful culture.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I do look forward to them and I am grateful you chose to share them.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Intervening, even relatively passively can have unexpected consequences however well intentioned, can’t it? On balance leaving the status quo to itself can enable genocides and persecutions . But that is at the bloody obvious end of the intervention spectrum and there are many shades of grey between that and the more egregious examples like us in Iraq supposedly to find WMD. But when it involves what you were trying to achieve, it should be applauded from the rooftops. Go you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Geoff. It is complicated, isn’t it? Looking only at the leprosy programme, I can feel some satisfaction – we set up clinics, patients were found and treated and the disease brought under control. All that, though, doesn’t happen on its own – people have different expectations (some impossible to meet) and trying to understand how a different culture works and operate within that. Still, I would not have missed my years in Afghanistan for anything.

LikeLike

Pingback: MarySmith’sPlace – lessons in cultural (un)awareness -Afghanistan adventures#44 | Smorgasbord Blog Magazine

Moving piece Mary with lots of thought. Personally, I don’t think you’d have been any the better having a psche degree. Empowering! 🙂 x

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Debby. It’s odd but those were the times – when I really had to stop and reflect on what I was doing there – which were the most difficult. Far more difficult than careering round mountain passes in a truck that felt it was held together by string!

LikeLiked by 1 person

LIfe altering moments for sure Mary. You’ve done well by documenting it all. I’ll bet when you look back you shake your head on how courageous you were. ❤

LikeLiked by 1 person

Your post and the discussion it prompted have given me a lot to think about. I’m learning so much about Afghanistan from your posts.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much, Liz. I am enjoying sharing these posts, even the uncomfortable ones, and always hope I’m providing an authentic glimpse into life in Afghanistan.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re welcome, Mary. What is very apparent to me from reading your Afghanistan posts is how little I know about how other parts of the world live. You’re doing a real service by chronicling and reflecting on your time there.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you. Of course, Afghanistan is vast and there are major ethnic differences so if I’d worked in say, Kandahar, which is a Pashto area, my views would be different.

LikeLike

What a sad situation they had and have. Now i think i have a little better understanding about the very difficult cooperation normal people there are practicing with the Warlords, and other criminals. Our Western military intervention uses billions for rockets and ammunition, but a very small amount for giving them food. Thank you for sharing another great sequel, Mary. Be will and stay save. Michael

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Michael. The situation could have been so different if, when the Soviets left, the Western countries (USA and UK in particular) had put resources into building roads and other infrastructure that would have allowed Afghan people to rebuild their lives. Instead, they turned their backs. Then America supported the Taliban because they thought Taliban would stop the various factions fighting. See where that got them!

LikeLiked by 1 person

That sounds so sad, and what should the people there think about such actions? Thank you for documenting this. Responsible humans too often try to forget too fast.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Another thought-provoking post, Mary..what shines through is something no degrees can teach you..how you cared and tried to understand… it must have been sad and so frustrating at times. I have learned since living here that having nothing means just that… which it doesn’t to us …we have often said I need to go shopping we have nothing to eat when what we really mean is we just want to stock up and buy more of what we fancy…To some people here they live from day to day, it’s as simple as that and it is probably the same in Afganistan and other countries…a sad fact of life…But the overriding feeling I get from these posts is that you cared deeply and many people you encountered will not forget you for that…A sobering post for us westerners …Hugs xx

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Carol. You are right about when having nothing means just that. I know I’ve opened the fridge, looked at the full shelves and declared we have nothing to eat – when I mean there’s nothing there I fancy. I remember Sughra’s absolute joy when I bought some cloth for a new outfit for her. A new dress never brings us such sheer delight!

LikeLike

Absolutely Mary.. we brought a little girl a dress and some shoes when we first came here and she slept in them.. she is now grown up but she remembers those pretty shoes x

LikeLiked by 1 person