Lad-sar-Jangal Winter 1989

Qurban’s wife, Masooma, had taken their two daughters to Pakistan to visit her parents, who had not yet seen their grandchildren. She was expected to return with Jon when he came to collect me. In the evenings I sometimes joined Qurban in his room where we talked late into the night catching up on news.

Qurban had spent much of his life in Karachi and was eager for news of friends there, and to reminisce about his days at the leprosy training centre and hospital. Although I had known Qurban quite well during his student days he had never talked much about his early childhood in Afghanistan. During one of our late night sessions he told the story of the horrors of those days when, at the age of about seven he contracted leprosy.

He had known of the disease as his paternal uncle had leprosy. In those days, people were terrified of leprosy, believing it to be incurable. As no-one understood its cause all kinds of misconceptions and myths surrounded the illness: it was a curse of God, a punishment for sin. Qurban’s uncle must have done something dreadful to be punished in this way, a bad person, to be avoided. He had been ostracised by the community, forced to build his house far away from the village. He wasn’t allowed to pray in the mosque.

One day as Qurban was returning from the village school he and some friends had stopped to play in the river. A friend pointed to a light coloured skin patch on Qurban’s leg, asking what had caused it. Qurban hadn’t noticed the patch before. When his friend poked it with a sharp stick he felt no pain. In that instant he understood. His uncle had several similar patches with no feeling on his body. Qurban went home but said nothing to his family – hoping the patch might disappear as mysteriously as it had come.

Eventually he showed the patch to his father. ‘It was the first time I had ever seen my father cry. I didn’t know grown up men could cry. His tears frightened me more than anything.’ His father warned him to say nothing to anyone. They began a round of visits to doctors, healers, mullahs, wise women – anyone who might have the means of making the patch disappear. Nothing – not the ointments, pills nor injections, made the slightest difference. Prayers, visits to nearby shrines and tawiz (a few lines of the Quran stitched into a cloth bag and worn as an amulet) were all equally ineffective.

Despite the misery and fear he felt while his parents searched desperately for a cure, Qurban was still a child, with a child’s resilience and enjoyment of life, delighting in leading his friends in mischief. One day he boasted that he could stick pins in his leg and feel no pain. For a few minutes he had basked in the admiration of his friends at this strange and wonderful feat. Next day his world collapsed.

‘At first I didn’t understand what had happened. No-one at school would talk to me but I knew they were whispering things about me. After school, for the first time in my life, no-one would walk home with me. But a crowd of boys was following me. I wanted to run, but I kept walking normally. Suddenly a stone hit my back, then another and another and the boys were shouting “Leper, leper!” Then I ran.’

Qurban’s school days were over, his childhood had ended.

Band-i-Amir – one of the most beautiful places in Afghanistan

One day Qurban’s father took him to the shrine at Band-i-Amir. This chain of five lakes, or dams, is said to have been created by Ali, son-in-law of Muhammad (PBUH). The waters are reputed to have healing powers. Qurban was excited about travelling so far, convinced that this time, surely, he would be cured.

Wondering whether he was to drink the magic water or wash the patch in it, he heard a splash. Turning, he saw threshing arms and legs churning the water. A young girl, a rope tied about her waist, had been thrown into the lake. He watched, horrified, as she was finally hauled, gasping and spluttering back onto the bank. She lay vomiting onto the shore while the people surrounding her murmured prayers.

Taking to the curative waters. This photo was taken in 2006 when I returned to Afghanistan

Convinced he would die Qurban became hysterical, begging his father not to throw him in the water. His father agreed that they should go first to pray at the shrine before Qurban underwent the “treatment”. The child’s sobs attracted the attention of a stranger who paused and peered at the patch on his leg. ‘That is leprosy,’ he announced. ‘You will never cure it like that – better go to Pakistan. They have medicine for this. My wife’s cousin was cured there.’

The shrine at Band-i-Amir I think that might be my son standing in the foreground!

Qurban had wanted to go immediately. Not realising that Pakistan was another country, he couldn’t understand why his father, although excited by the news, did not seem particularly anxious to set off on another journey to buy the medicine. ‘He struggled for months to raise enough money for the trip,’ he explained. ‘And he had to make arrangements for someone to care for my mother and the land. All this time I hated my father because I thought he had decided not to go.’ Qurban paused, blinking back sudden tears, before continuing: ‘I was seven years old, quite a big boy, but all the way to Pakistan, I complained about being too tired to walk. My father carried me on his shoulders most of the way.’

Even when they reached Quetta their troubles were far from over. Many Hazaras had already settled in the city and they soon made contact with people from their own area – but no one had heard of a cure for leprosy. Soon they were caught up once more in a round of visits to doctors, whose prescriptions were useless and expensive. His savings soon vanished and Qurban’s father had to find work. Not far from Quetta he found a job as a coal miner; back breaking work digging for coal in a series of open cast mines and tunnels running deep into the side of the mountain.

One day their luck changed. They met a doctor who not only recognised Qurban had leprosy, but knew of the hospital in Karachi where it could be treated. He wrote a letter of referral to a doctor there. Within days, Qurban and his father had made the journey to Karachi and Qurban had been admitted for treatment in the large Manghopir hospital on the outskirts of the huge city. His father left him almost immediately to return to Lal.

Qurban grinned, ‘The rest you know – school, training, marriage and back to Afghanistan.’ I realised, however, there was a great deal about Qurban I really didn’t know at all. Although completely cured of leprosy, the memory of those stones thrown by his school friends so long ago had marked him deeply. Those little boys, grown up now, had welcomed Qurban back into the community – showing him acceptance and respect. But Qurban’ feelings of insecurity and lack of confidence made him question what the community really thought of him.

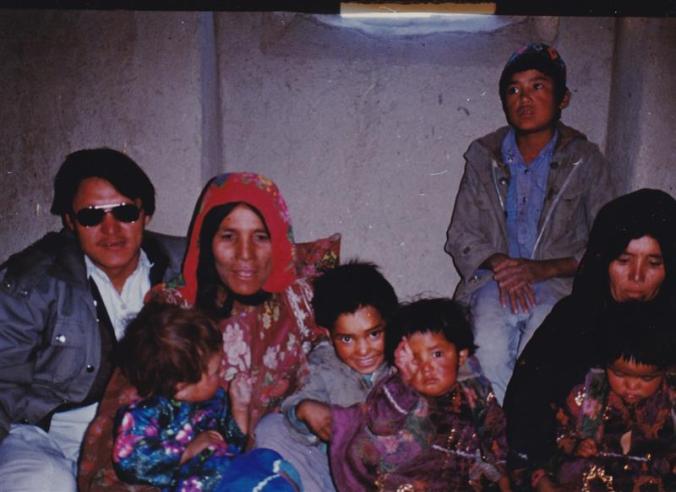

Qurban in dark glasses even with his family.

Convinced everyone who looked at him saw immediately, in his loss of eyebrows, the stigma of leprosy, he had affected the habit of wearing dark glasses at all times, even indoors. He suffered periods of moody introspection, which could last for days, during which he would talk to no one, followed by a sudden cheerful gregariousness. His sudden mood swings left everyone confused. Qurban admitted he could do nothing to fight off the black clouds of depression which descended on him without warning.

A story of a challenge so well told, Mary. Thank you

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, John. It’s hard for us to imagine the stigma attached to leprosy – not so very long ago, either.

LikeLiked by 2 people

It must have been heartbreaking to become infected. To have a child infected would be the worst.

LikeLiked by 2 people

One of the reasons I wanted to work on the leprosy project was a young Afghan girl I met when I went to Pakistan on holiday. I visited the leprosy hospital (I worked in the UK for Oxfam who gave some funding to the hospital) and met Zakia and heard her story. When her family in Afghanistan realised she had leprosy they were afraid the villagers would throw her out of the village so they hid her in an outhouse. By the time a team from Pakistan came to carry out leprosy checks, Zakia was horrifically deformed – no nose, eyes unable to blink, fingers and toes shortened. She was taken to the hospital in Karachi and given treatment. When I met her she was waiting until her condition had stabilised and then a surgeon would start reconstructive surgery. I was so bowled over by her cheerfulness and positivity – she wanted to get married, same as any young girl. It made me want to do something useful to help others like Zakia. The great thing is she did undergo reconstructive surgery (the only kind of nose job I approve of) and she did get married. Goodness, nearly another blog post as a reply! Yes, to have a child infected is the worst and you do anything to try to keep then safe.

LikeLiked by 6 people

This is a story worth sharing, Mary. Have you written it up somewhere?

LikeLiked by 2 people

No, I haven’t. Maybe, I will one day.

LikeLiked by 2 people

😊

LikeLiked by 1 person

I would encourage you to do that. Qurban’s story is compelling.

LikeLiked by 1 person

His father had to love him greatly to go through all that.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Yes, indeed. It must have been heartbreaking for him to leave his son behind in Pakistan to return to Afghanistan where the rest of his family needed him.

LikeLiked by 3 people

We really do not know just how lucky we are. Walking to Pakistan, working in mines to pay for treatment that would be free here. Such amazing resilience is to be applauded and congratulated. Another fine episode, Mary.

Best wishes, Pete.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you, Pete. As you can imagine, life for those coal miners was horrendous – filthy work, low wages and absolutely no health and safety regulations. And all the time worrying if he would ever find a cure for his son’s leprosy and how the rest of the family was managing without him. Even with the current pandemic threatening us we are so very lucky.

LikeLiked by 4 people

Well said, Pete!

LikeLiked by 1 person

What an interesting story and the photos are beautiful, no wonder people would believe in the healing powers of the water.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Band-i-Amir is really beautiful and the colours of the water are amazing, thanks, I believe, to many different mineral deposits. I’ll post something more about it later.

LikeLiked by 3 people

I look forward to it!

LikeLiked by 1 person

What an amazing triumph. Your reasons for helping are so altruistic and beautiful. Hopefully more people were helped as treatments became available. I often hold my breath while reading your posts. They are so emotional and my heart goes out to all involved. Thank you for sharing your experiences.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you, Lauren. I am very happy to share my experiences as it gives me the chance to wallow in my memories – from a comfy chair at my desk!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Memoreis are great. It is wonderful that you have such rich ones.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Mary , again I am bowled over by your on going story. So apt is this post of s father’s love as I read it on father’s day. Such sacrifice, and Qurban paid back his recovery by training and helping others. You say his father left him in the hospital when he was seven to get back to the rest of his family. Did Qurban stay in Pakistan until he was fully trained, that would of taken years, how would he survive. I hope he saw his father again. … Lots of questions but it’s so interesting.💜

LikeLiked by 4 people

Thank you, Willow. Yes, Qurban stayed in Pakistan until he was trained. In the area around the hospital where he received treatment a lot of Hazara people are living, some of whom would be relatives so he was looked after. When he finished school he trained for two years as a leprosy technician – a paramedic with specialist knowledge of leprosy – also working in the hospital. I met him in Pakistan when he was a student and was at his wedding. Soon after he married he went back to Afghanistan to set up his leprosy clinic. He was still very young to have so much responsibility.

LikeLiked by 4 people

Gosh so he left home at seven, such a difficult and different way of life to ours. As you say so much responsibility so young.

His father did so much to get him treatment and probably never saw him again until he returned to Afghanistan as a man. Would they ever received word of eachother I wonder. Such sacrifice.

LikeLiked by 2 people

The resilience of the people is amazing, Querban’s Dad was a hero, I hope Querban appreciated him.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Qurban did appreciate what his dad did for him, especially when he was older and looked back on the trek to Pakistan and his dad’s work in the coal mines to pay their way. You are right about the resilience of the people. It’s why I never give up hope for Afghanistan – no matter what gets thrown at them, they somehow keep going.

LikeLiked by 2 people

What a fabulous story of a father’s love! Perfectly timed post.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks, Barb. I hadn’t even planned it to coincide with Father’s Day. A happy accident.

LikeLiked by 2 people

What a wonderful story. I can see how the effects of being ostracized as a child would linger and cause depression.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks, Darlene – and non-existent mental health care services.

LikeLiked by 2 people

such a poignant story, Mary. So much I didn’t know about leprosy, though in those odd coincidences I was at a church in Dunwich on the Suffolk coast where they still have the remains of a medieval leprosy hospital. I hadn’t realised it was a thing in the UK

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks, Pete. It fit nicely for Father’s Day. Yes, there were a number of leprosy hospitals around the country and the ‘lepers’ as they were called in those days had to ring a bell to warn people of their approach. It was a very misunderstood illness for a long time – and still is in some parts of the world – because people didn’t know how it was spread.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Sorry for calling you Pete, Geoff. I did know it was you 🙂

LikeLike

What a story Mary, and such an amazing man.. not just to go to such lengths to cure his son but to do so in the face of the stigma attached to the disease. Thank goodness he finally managed to get passed the charlatans and find the hospital. I am sure it must have had a lifetime impact on Qurban but it makes him all the more special that he devoted his life to treating those who suffered from it. Pressed for later today..xxx

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks, Sally. Yes, Qurban never got free of the impact of the stigma – no counselling services available to help either. Thanks so much for sharing the story.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Delighted to Mary.. enjoy the rest of the weekend. x

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s very, very wet here!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Here too… sudden violent downpours, winds and low flying sparrows! x

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: MarySmith’sPlace – Afghanistan adventures#40 | Smorgasbord Blog Magazine

Qurban is blessed to have a caring father. It’s good to see he grew into a handsome man with a family of his own. The waters of Band-i-Amir are so blue!

LikeLiked by 2 people

I thought he was a very handsome young man. And, yes, those waters of Band-i-Amir are truly astonishing from the bluest of blues to green and aquamarine.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Such a powerful piece, Mary. The horror of the reactions of others, the child thrown into the water, the strength and commitment of his father and Qurban coming full circle to help others in the same situation. You’ve witnessed such a range of experiences that really put people to the test.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you, Trish. I was lucky to spend enough time in Afghanistan to see beyond the stereotypes depicted in the news stories to the real people.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I love the humanity in your stories Mary. ❤

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you, Debby. I love being able to share those stories.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you 🙂 xx

LikeLiked by 1 person

I love having the opportunity to read your stories, Mary.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Liz.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re welcome, Mary.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on Judith Barrow.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Many thanks for reblogging, Judith – much appreciated.

LikeLike

It’s a very heart-crushing story. Now, with this virus, we have another thing about which there are a lot of conspiracy theories, and maybe there will be people who are being discriminated against again.

Unfortunately, we are not so far away from old superstition in Europe either.,

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, you’re right, Michael. The conspiracy stories are already circulating. Before anyone knew the causes of leprosy, many of the (wrong) ideas people had were their way of trying to explain the reasons for something they didn’t understand.

LikeLiked by 1 person

So true, Mary, and bad enough.

LikeLiked by 1 person