We pulled up outside a flat roofed, mud built house, its window frames painted a cheerful blue. Here we would live and work until the permanent clinic, already under construction, was complete. Three people hurried out and I was introduced to Ali Baba, the clinic chowkidar (watchman) who, in halting English made a little speech of welcome to which I replied in hesitant Dari. Baqul, the cook, grinned, shook hands and disappeared to organise tea. It was some weeks before I learned that his given name was Ali Ram, and that every time I called him Baqul I, along with everyone else in the village, including his children, was addressing him as “Old Man”. The third member of the team, Ismail, the field assistant, needed no introduction as we had met in Karachi.

Standing at the highest point in the village, the house looked over a view of golden wheat fields beyond the edge of the village whose houses were spread out in a large semi-circle around a central well. Orchards of mulberry, apricots and peaches had roses blooming between the trees and all around rose the mountains, their peaks piercing a brilliant blue sky. I could just catch the musical sound of a mountain stream rushing over its stony bed and, from further off, the tinkle of goat bells was accompanied by the reedy piping of the goatherd. I fell in love.

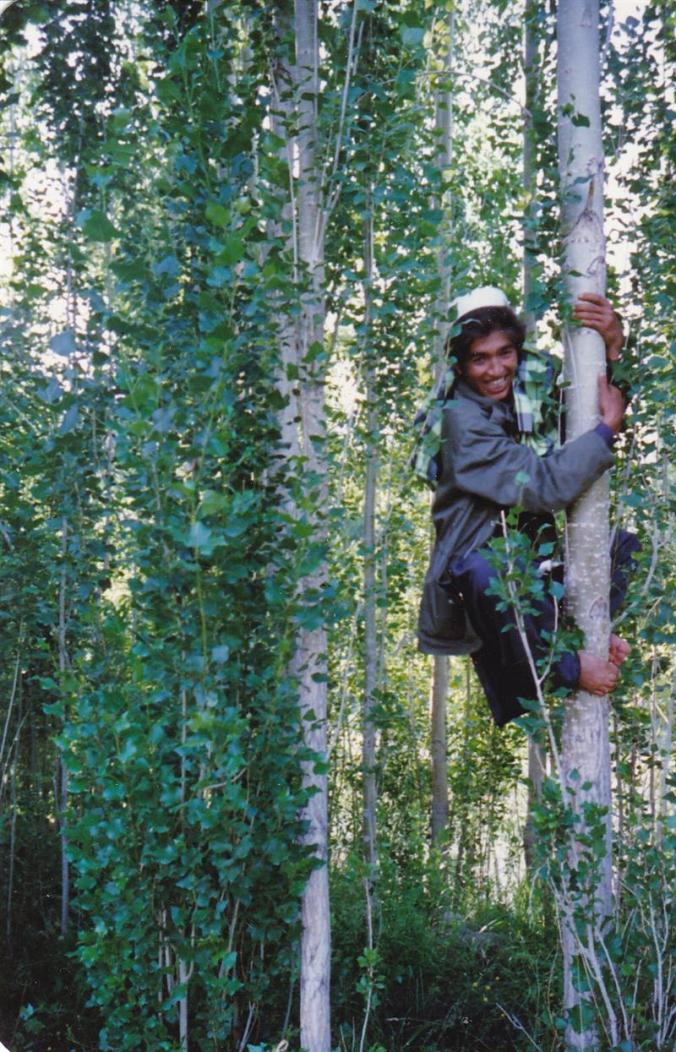

Hussain when in a good mood.

Through a doorway on the left of a hall was a large room, barely half the mud floor concealed under striped gilims. A few mattresses and a pile of bedding made up the sole furnishings. Light flooded the room from the huge windows on two walls. This was the staff room. The kitchen, by contrast, was gloomy, the only light coming from two tiny windows set high up in the wall. In one corner Baqul already had a bucket of water for our baths simmering on his wood burning stove. Half the room was used for storing firewood, tools and kerosene. A small area, partitioned by a head high wall of loose stones was the bathroom. An assortment of gilims covered most of the floor of my room and a small metal folding table had been placed, with a folding chair, below the window.

Hussain dreaming of a Toyota – but making do with a donkey!

By the time Baqul announced the bath water was ready I had unpacked. Noting the gaps between the stones of the makeshift partition in the bathroom were used as shelves – here a razor, there a tube of toothpaste, here a bar of soap – I selected spaces for my own toiletries and began to feel quite at home. Two buckets, one of steaming hot, the other of cold water sat side by side on a plank of wood supported by two stones. Next to the buckets was a round metal bowl with which to pour the water over me. I later discovered the original purpose of this water pourer. Whenever someone washed his hat – the round, white cap, sometimes embroidered, worn by almost all men in Jaghoray – the damp headgear was stretched over the bowl to retain its shape while it dried.

Refreshed by my bath, replete with mulberries and tea, I lounged on a mattress, idly chatting to Ismail, planning walks on the mountains and generally behaving as though I was on holiday.

Hussain, returning from his bath, announced: ‘We need a planning meeting.’ Not a holiday, then.

Medicines and equipment for the clinic had been despatched earlier from Quetta in Pakistan and were now awaiting collection at the field hospital, close to the bazaar in which we’d stayed overnight. We would have to unpack, check and count everything as well as making the house ready for use as a clinic as soon as possible. Hussain’s major concern was that work on the new building proceeded quickly.

‘It means,’ he pointed out, ‘I shall have to go to the building site often. If I don’t go the workers will go slowly.’ I nodded. Made sense. He continued, ‘Which means I need transport.’ I nodded again. It was true; the work couldn’t be done effectively without a vehicle for fetching and carrying and, later, for leprosy touring work. However, until the Programme Co-ordinator, Jon, arrived later, we did not have money to buy a vehicle. Even then, there wouldn’t be enough to buy the fancy Japanese make after which Hussain hankered.

‘Until Jon arrives you’ll have to hire a jeep as and when necessary. When he brings money you should be able to buy a decent second hand Russian jeep.’ My encouraging smile was met by a petulant scowl.

‘I don’t want a Russian jeep, some old thing which will be always breaking down and needing repairs. If you want me to do my work properly you should buy a proper vehicle – like a Toyota.’ This wasn’t a discussion about how to carry out the work effectively, but about status symbols and image bolstering.

‘Hussain, we don’t have the money to buy a Toyota. Use what funds Jon will bring to buy a good condition Russian jeep and maybe we can include an estimate for a better vehicle in next year’s budget.’ Still Hussain was mutinous, ranting about how useless Russian vehicles were, always breaking down, using petrol which was more expensive than diesel. Finally, having worked himself into a tantrum, he stormed out.

Ismail and Ali Baba looked as uncomfortable as I felt. I shrugged, ‘I think the meeting has been adjourned. I’ve brought coffee – anyone want one?’ This met with approval, especially from Ismail who’d developed a coffee addiction while in Pakistan. He made it with such quantities of powdered milk and sugar it resembled a hot coffee milk shake.

Hussain re-joined us and was soon smiling though I suspected it was only a temporary truce and was uneasy at this stubborn and childish aspect of his character. As daylight faded, Ali Baba lit the pressure lamp, known as the gaz. Before the curtains were drawn red lights arced across the night sky. ‘Are those what I think they are?’ I asked apprehensively.

‘Tracer bullets,’ replied Hussain nonchalantly, good humour completely restored by my alarm. ‘Hisb-i-Islami is on that mountain. They just fire off rounds from time to time to remind people they are there. Sometimes there is fighting between the parties but not now.’

The Soviets had left Afghanistan in February, five months earlier, but President Najibullah, considered by many to be their puppet, was still in power in Kabul. The mujahideen were not finding it as easy as anticipated to dislodge him. Although Jaghoray and neighbouring Malestan were free districts, meaning they were held by the mujahideen, the Provincial capital, Ghazni was still under Kabul Government control.

Apart from Hisb-i-Islami drawing attention to themselves on their mountain top there were several political parties in the area: Nasre, Seepa, Nezhat and Ittehadia. The latter had once been the party of most influence and power in Jaghoray and had been the protectors of the French organisation Medecins sans Frontiers who ran the field hospital. They had also been instrumental in re-opening schools in the area, eliciting financial support from Germany, but corruption amongst the party leadership eventually eroded its credibility. Occasionally, parties had tried to form a coalition but no alliance had been long lasting. Now, Nasre was indisputably the strongest party in the area, their nearest rivals in fighting strength, Hisb-i-Islami, having been routed in the last skirmish a few weeks before.

‘But what do these parties fight about here?’ I asked. ‘I thought the mujahideen were all fighting against Najibullah’s Government around Kabul and the other big cities?’

Ismail replied, ‘Everything here is a different from Kabul. The parties here are too busy fighting each other to fight the Government. In Bamiyan, the parties are more organised, they want to work together, but not here.’

Baqul began to gather up the tea glasses and I headed for the latrine some yards away before retiring for the night. The air was pleasantly cool, the village silent. From one or two houses a faint light flickered, otherwise there was total darkness. I risked breaking my neck on the uneven, stony ground as I gazed upwards in wonder.

Hussain was waiting in my room. ‘I brought you a lamp,’ he said indicating the paraffin lamp he’d placed on the floor. ‘Keep it on the floor, not on the windowsill – in case they shoot at us from the mountain.’ I laughed, then realised he was serious as he checking and double checked the windows were closed. ‘You must be very careful here. This is not my village. I don’t know the people so we don’t know who we can trust.’

Although I was sure he was exaggerating the risks, he looked so solemn I hid my smile. I was too tired to stay awake worrying about possible dangers, whether real, or imagined only by Hussain. Busy days were ahead.

If you are enjoying these instalments from my first journey to work in Afghanistan you may also enjoy Drunk Chickens and Burnt Macaroni which covers the last three years of my time there.

.

I am indeed enjoying it!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m delighted. Thanks so much, Jemima.

LikeLike

seems like you’ve got good people looking out for you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, Jim, I was lucky to live and work with soem wonderful people. I did meet some not to good oens along the way but the good ones outweighed the bad. Thanks for coming along on the journey.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m loving the journey!

LikeLiked by 1 person

The interesting political complexities of the time. Your account is much more informative than those I used to read in The Sunday Times back then.

Best wishes, Pete.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Pete. I wasn’t sure how much political stuff to include and actually cut out bits. For instance the leader of the Ittehadia group absconded to Pakistan with funds given to them for schools. He stole one of our vehicles – which had been dnated by the late Pakistan President Zia. In Pakistan, in Islamabad he set up a bakery business which was so successful he opened branches in other cities. Eventually he and his family went to America. I think I saw things differently from the journalists because they talked to political leaders, mujahideen commanders and fixers whereas I spent my time living with ordinary people far removed from the influencers.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Mary, the orchard, fruit, stream and goat bells sound idyllic…then modern warfare in the distance! What a dichotomy! I’m loving this series and will add your non-fiction books to my reading list!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks, Annika. Fortunately, the warfare was usually in the distance – but it was almost always a background to everyday life.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Enjoying your (our) journey, Mary.

Lynn

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Lynn.

LikeLike

A lovely installment of your time in Afghanistan. A place I know I will never visit as when I finally get to live in England, I am never leaving Europe again. Your friend Ismail drinks his coffee just like I do, Coffee flavoured milkshake.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks, Robbie. At least you can make a ‘virtual’ visit to Afghanistan! Ismail’s coffee making was legendary.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Virtual is terrific, Mary. I must read this book of yours. I am really interested just not as brave as you about visiting politically unsettled places.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You live in South Africa – not the most politically settled of countries!! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Travels in Afghanistan (5) ~ Mary Smith | Sue Vincent's Daily Echo

Were you a doctor or nurse with the Doctors Without Borders program, Mary? This is so interesting!

LikeLiked by 1 person

No, not a doctor but a sort of paramedic trained in leprosy work. I worked for three years in Pakistan at the leprosy headquarters in Karachi, setting up a health education department, primarily to raise awareness of the disease and that it is treatable. After those three years I signed up again for Afghanistan. Glad you are enjoying it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Is it prevalent in those countries, then?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Leprosy was fairly prevalent in Pakistan when I first went out there in 1986 but, thanks to the multi drug therapy and awareness, it is now under control. That means the occasional new case may still be found but it’s not longer a problem. In Afghanistan, the cases were mainly found amongst the Hazara people of central Afghanistan. I don’t know why they were/are more susceptible than other tribal groups such as Tajiks or Pushtoon. In both countries, TB is much more of a problem.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Interesting- and sad. I wonder if it could be diet related? It looks fairly aride from your photos. Is fresh water an issue? Sorry, I’m asking so many questions!

LikeLiked by 2 people

I’m delighted you have questions to ask. Much of Afghanistan is very arid and there is little rain in the summer months. In the Hazara Jat region, farmers depend on snowmelt to irrigate the fields. However, I think the susceptability to leprosy is more likely to be genetic.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you, Mary ❤

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wonderful writing ~ the beauty of the world never ceases to amaze me, and this story of your early experiences in such a wonderful and beautiful land makes me long to take part in the adventure. I can understand how you could fall in love with this place, even within the political turmoil and even worse the fighting all around. You’ve experiences something very special and it shows in your writing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much. I’m delighted you enjoyed the post. I’m trying to post an instalment once a week about the first six months I spent in Afghanistan. It feels a bit self-indulgent, wallowing in memories. It is an amazing country – pulls you in and never lets go.

LikeLike

There is nothing better than wallowing in memories ~ the best way to time travel 🙂 Especially when it can take you back to a place, an amazing country, that hold a piece of you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I came back to give this a second read because there is so much here. I’m enjoying this, Mary.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Rob. On this first trip to Afghanistan I was there for six months and hope to put up a post each week. Reading over diaries I realise there are no big dramas – but for me every day was exciting in its own way.

LikeLiked by 1 person